I recently completed two books by two very different authors, Douglas Rushkoff and Benjamin Wiker. However, the serendipitous fact that I read them one right after the other brought home to me some intriguing commonalities between the two, focusing particularly on the widespread societal effects of social darwinism.

The two books are:

Although I suspect that these two authors would be very far apart on political issues, my reading of these two books in juxtaposition emphasized two interesting commonalities:

- Both authors comment on the origins and dangers of social darwinism.

- The two authors both focus their historical analyses on roughly the same time period, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

In writing the above, I also came to an interesting realization on another more-subtle commonality: Wiker starts with the classic cynical treatise The Prince, by Niccolo Machiavelli. Rushkoff starts with the Middle-Age “princes” who created the corporation and imposed central currency in Europe.

Rushkoff’s premise is that the aristocracy in the Middle Ages devised the chartered corporation as a legal mechanism to give them control over commerce and wealth. Because of their privileged status granted by government, corporations have progressively gained more power, even becoming legal “persons” over time.

Rushkoff’s criticism is that Western society has become steeped in corporatism, and that this pits individuals against one another in a win-lose competitive struggle. People operate according to unconscious corporatist values and assumptions about how life should be and are prevented from connecting in a natural way through communities.

Wiker’s premise is that modern civilization has been affected by a materialistic, atheistic philosophical tradition preserved and promoted by a series of highly-influential thinkers and their books, starting with Machiavelli, then Thomas Hobbes, Rene Descartes, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, Margaret Sanger, Margaret Mead, and Alfred Kinsey, along with others along the way.

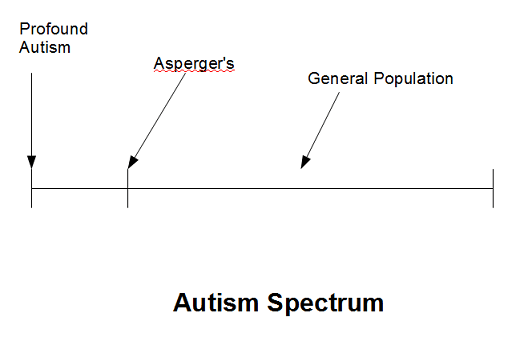

As I said, where I see an important commonality between Rushkoff and Wiker is when it comes to their implications and comments about social darwinism: The modern world is strongly influenced by the idea that the natural order demands that the strong survive and the weak die off.

Ruskoff writes,

Richard Dawkins’s theory of the “selfish gene” popularized the extension of evolution to socioeconomics. Just as species competed in a battle for the survival of the fittest, people and their “memes” competed for dominance in the marketplace of ideas.

Human nature was simply part of biological nature, complex in its manifestations but simple in the core commands driving it. Like the genes driving them, people could be expected to act as selfishly as Adam Smith’s hypothetical primitive man, “the bartering savage,” always maximizing the value of every transaction as if by raw instinct.

Ironically, says Rushkoff, religionists were used to promote a compatible economic regime:

Right-wing conservatives turned to fundamentalist Christians to promote the free-market ethos, in return promising lip-service to hot-button Christian issues such as abortion and gay marriage.

It was now the godless Soviets who sought to thwart the Maker’s plan to bestow the universal rights of happiness and property on mankind. America’s founders, on the other hand, had been divinely inspired to create a nation in God’s service, through which people could pursue thier individual salvation and savings.

Rushkoff contends that

What both PR efforts had in common were two falsely reasoned premises: that human beings are private, self-interested actors behaving in ways that consistently promote personal wealth, and that the laissez-faire free market is a natural and self-sustaining system through which scarce resources can be equitably distributed.

Wiker follows the development of atheistic social darwinism from Machiavelli, but he takes considerable time to establish the connection between Darwin and eugenics. On pages 88 to 89 of 10 Books he quotes from Darwin’s Descent of Man (not as well known as On the Origin of Species):

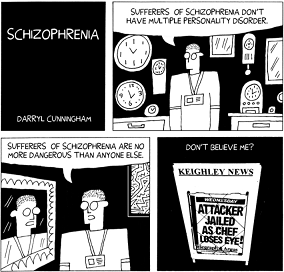

With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health …. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination [by means of various works of charity and relief]. Thus the weak members of civilised societies propagate their kind ….

If … various checks … do not prevent the reckless, the vicious and otherwise inferior members of society from increasing at a quicker rate than the better class of men, the nation will retrograde, as has occurred too often in the history of the world.

Wiker argues that the writings of Darwin and other atheistic thinkers have led to a modern world in which the weak are seen as expendable for the good of human progress.

At the end of his book, Wiker comments:

We are so fond of thinking of our progress from the simple savage that we forget to take account of whether we are really progressing in some sort of virtue or rather becoming more complexly and deviously savage.

We have a higher regard for health than our ancestors did, and a far greater knowledge of biology. But when biology, rather than theology, becomes the queen of the sciences, then Christian prohibitions against eugenics, the elimination of the unfit or the unwanted through abortion or infanticide, or the elimination of diseased races or classes all become merely “medieval” and irrelevant.

Rushkoff and Wiker approach their analyses with very different objectives and foci, and it would be far from accurate to say that they reach the same conclusions.

But both Life Inc. and 10 Books That Screwed Up the World shine light on some of the historical and philosophical sources of the great streak of heartlessness evident in the modern world.

In about 1970, I was picked up hitchhiking on I-85 in North Carolina by an older fellow driving a sedan. We got into a conversation about the problems of the world. From his point of view, one of the biggest problems was welfare and charity — all the giveaway programs that are supposed to help the poor.

I raised the question, Well, what are they supposed to do? Suppose they need help to survive and get back on their feet?

His response was, “Who cares? Let ’em die. That’s the way nature works.”

I wonder who he had been reading.

AB — 4 September 2009