Reading Andrew Robinson’s fascinating book Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts (2002, McGraw-Hill), I recently learned the amazing story of the decipherment of the Linear B script by amateur philologist Michael Ventris in the 1950s.

The story brings home some important lessons about innovation:

- Be willing and eager to collaborate

- Take advantage of cross-fertilization by bringing in perspectives and skills from diverse disciplines

- Fight against your personal prejudices and keep yourself open to new ways of looking at things

Linear B is a script discovered on the island of Crete by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. Evans never deciphered Linear B, as he had fallen too much in love with certain precious ideas, chiefly his belief that the culture he had uncovered through his excavations at Knossos was a great noble civilization (which he called “Minoan”) that had dominated the Aegean in ancient times.

As it turned out, Linear B was a syllabic script used to write ancient Greek. However, the decipherment of the script was delayed by many decades because Evans was reluctant to share the inscriptions with other scholars.

When death finally wrested the inscriptions from Evans’s hands in 1941, other scholars were able to begin a concerted effort at decipherment.

Although it was Ventris’s genius primarily that cracked the script, he didn’t do it alone, which is a crucial point.

Although a brilliant scholar with a lifelong fascination for Linear B, Ventris was in fact not a professional philologist or linguist.

Ventris was an architect, and I think his architectural training, discipline, and practices were an important contributing factor in his success with Linear B.

Ventris was an architect, and I think his architectural training, discipline, and practices were an important contributing factor in his success with Linear B.

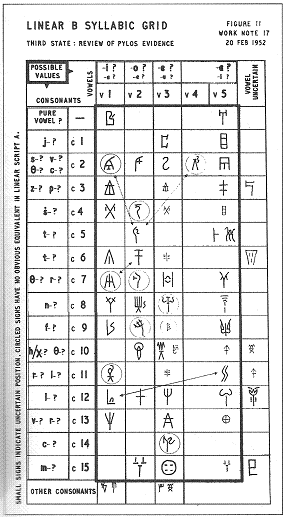

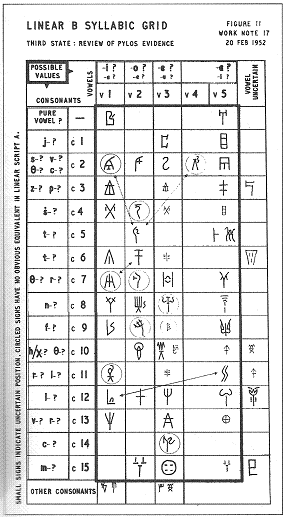

It’s interesting to note that Ventris’s grid-based system for decipherment is reminiscent of the schedules architects use to lay out information in their drawings.

But more important for Ventris’s success with Linear B was his value of collaboration, also an important architectural practice.

Robinson quotes classicist Thomas Palaima describing Ventris’s practice of “group working, hypothesizing and brainstorming” and adds that

In other words, he did not believe in the idea of the genius who works solo and finally solves a problem by his own sheer unaided brainpower …

Ventris explained in writing and in tremendous detail each stage of his attack on Linear B, and then circulated these neatly type “Work Notes” (Ventris’s name for them) to other scholars for comments and contradictions.

Much of what he hypothesized turned out to be irrelevant or wrong, but this did not stop him from showing it to the professionals. And it appears that he did take this whole approach from his work as an architect.

To me this stresses the immense value of multi-disciplinary teams, cross-fertilization, and collaborative approaches in all kinds of innovation work.

Also important was Ventris’s humility and willingness to recognize his own errors, in contrast to Evans’s stubborn insistence on his Minoan theory.

Ventris and other scholars had for a time favored the idea that Linear B was used to write the Etruscan language. However, after it became evident that the Linear B language was Greek, writes Robinson,

… in a measured and slightly diffident voice [Ventris] announced his discovery on BBC radio, publicly renouncing his long-cherished Etruscan hypothesis … As John Chadwick much later said of Ventris: “The most interesting fact about his work is that it forced him to propose a solution contrary to his own preconceptions.”

This is a worthy example for all experts, who are far too inclined to hop on a particular hobby-horse and just keep on riding it for their entire careers.

These lessons bring to mind some research that we have done at the Institute for Innovation in Large Organizations in the area of cross-functional teaming, a valuable process for innovation work.

(Most of our reports are limited-circulation and confidential. However, we do sometimes quote them as I will do here, and a few of our reports are available on request.)

Here are some points on the value of team diversity in product design from one of our reports:

Bringing people from many disciplines and functions together in design teams offers great potential as a strategy to produce innovative products. However, such diversity also lays the groundwork for conflict. Thus team leaders and company management need to manage team diversity so all members can be effective and make their contribution.

Mitzi Montoya, Zelnak Professor of Marketing at North Carolina State University (NCSU) and executive director of the Services and Product Innovation Management Initiative at the school, says that companies need to recognize the likelihood of conflict and miscommunication and “put processes in place that will manage that inevitable consequence.” The problems that arise from team diversity “have to do with how the organization is structured, who those people report to. It often has nothing to do with the project itself.”

Bob Pagano of Red Sky Insights points out that diversity can bring value to the product design process by putting blue-sky innovators in the same room with more hard-nosed practical players.

You’re going to have some people around the table who are really creative and are going to look at the assignment with a really open mind. You want to have some very creative people early on who might see something outside the normal way of doing things. If they say something really bizarre, we don’t necessarily want to discourage that.

But you also need some enforcers, the ones who are going to put up the barriers, the ones who will push back, but trying to reach a common ground. They might say, ‘Well, that’s interesting. Let’s see if we can do that within the rules on the retail end.’ It’s kind of a give and take to see that nothing gets overlooked.

In our ILO report, we also found that, aside from their contributions from a functional perspective, individual team members contribute different personal qualities to the life and work of a product design team. These different characteristics can offer value in unique ways and can come into play at different stages in the process:

Innovation consultant Stephen M. Shapiro, previously an Accenture consultant, believes that it is important to “understand the various innovation styles of team players” to make use of their distinctive strengths.

Speaking with ILO researchers, Shapiro explained how he classifies these styles:

Analytical people tend to be more focused on intellectual activities and often find flaws in everything.

Structured people want to know the plans and how things will be carried out. They also are a bit more critical but are more action oriented.

Creative individuals are cerebral yet like to think broadly. They are enthusiastic and generators of new ideas. But they are often poor at implementation.

Relationship-oriented people are needed to get anything done as they can engage the organization. But they often are too focused on consensus, which is a barrier to innovation.

Shapiro believes that “once people understand their styles and the associated strengths and weaknesses, they can be more effective in how they work together.” In his view:

The innovation process goes from analytical—define the problem . . .

to creative—define solutions . . .

to structured—define plans . . .

to relationship-oriented—engage the organization.

Thus, the various players’ personal styles can come to the fore at different stages of the group’s work.

But do team diversity and cross-fertilization translate into financial results?

Our work on this report suggested that that less diverse teams tend to produce better financial results overall than highly diverse teams. However, if the company is seeking high-value breakthrough results, it is more likely to achieve those through greater diversity in design team membership:

Lee Fleming, business administration professor at Harvard Business School, writes in Harvard Business Review that highly diverse, cross-disciplinary innovation teams introduce certain risks (“Perfecting Cross-Pollination,” September 2004). After researching 17,000 patents, he believes that

The financial value of the innovations resulting from such cross-pollination is lower, on average, than the value of those that come out of more conventional, siloed approaches. In other words, as the distance between the team members’ fields or disciplines increases, the overall quality of the innovations falls.

However, he adds a big but:

But my research also suggests that the breakthroughs that do arise from such multidisciplinary work, though extremely rare, are frequently of unusually high value—superior to the best innovations achieved by conventional approaches.

Fleming comments that “when members of a team are cut from the same cloth,” as with a group of all marketing professionals, “you don’t see many failures, but you don’t see many extraordinary breakthroughs either.”

However, as team members’ fields begin to vary, “the average value of the team’s innovations falls while the variation in value around that average increases. You see more failures, but you also see occasional breakthroughs of unusually high value.”

AB — 21 Nov. 2009