An interesting study, soon to appear in the Journal of Risk Research, by Yale law professor Dan M. Kahan and colleagues, suggests that people tend to disbelieve scientists whose cultural values are different than theirs.

I’m not able to determine when this study will be published, but you can find an abstract at this link, and I was able to download a preliminary version of the whole article in PDF by clicking on the link on that page that says “One-Click Download.”

These conclusions shed light on the debate over anthropogenic climate change, Kahan tells Science Daily (“Why ‘Scientific Consensus’ Fails to Persuade“):

We know from previous research that people with individualistic values, who have a strong attachment to commerce and industry, tend to be skeptical of claimed environmental risks, while people with egalitarian values, who resent economic inequality, tend to believe that commerce and industry harms the environment.

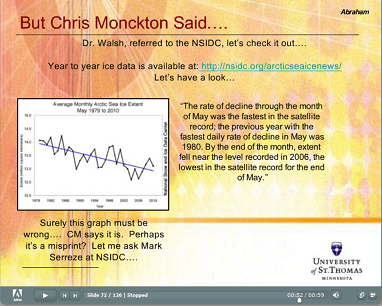

(For more on the climate-change controversy, see my previous entry, “John Abraham’s Point-by-Point Rebuttal of Climate-Skeptic Monckton.”

Kahan and colleagues based their study on the theory of the cultural cognition of risk. In his paper, Kahan says this theory “posits a collection of psychological mechanisms that dispose individuals selectively to credit or dismiss evidence of risk in patterns that fit values they share with others.”

The researchers surveyed a representative sample of 1,500 U.S. adults. They divided this sample into groups with opposite cultural worldviews, some favoring hierarchy and individualism, the others favoring egalitarianism and communitarianism.

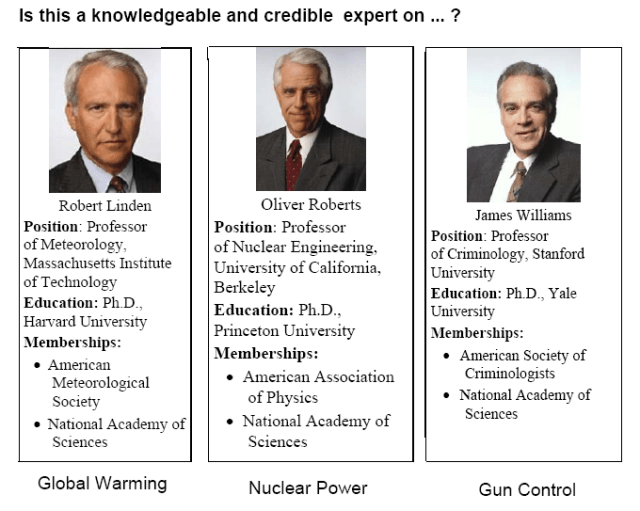

They surveyed the respondents to determine their beliefs about what in fact is the scientific consensus on issues of climate change, disposal of nuclear waste, and concealed handguns, with particular focus on the associated levels of risk in each of those areas. Various statements were attributed to fictional personas portrayed as authors of books on these various issues. Respondents were asked to judge whether each author is really an expert or not.

Analysis of the results on the climate-change issue revealed that:

Analysis of the results on the climate-change issue revealed that:

Disagreement was sharp among individuals identified (through median splits along both dimensions of cultural worldview) as “hierarchical individualists,” on the one hand, and “egalitarian communitarians,” on the other. Solid majorities of egalitarian communitarians perceived that most expert scientists agree that global warming is occurring (78%) and that it has an anthropogenic source (68%). In contrast, 56% of hierarchical individualists believe that scientists are divided, and another 25% (as opposed to 2% for egalitarian communitarians) that most expert scientists disagree that global temperatures are increas-ing. Likewise, a majority of hierarchical individualists, 55%, believed that most expert scientists are divided on whether humans are causing global warming, with another 32% perceiving that most expert scientists disagree with this conclusion.

The study revealed similar results around the issues of geologic isolation of nuclear wastes and concealed-carry laws.

So should we conclude that people are going to believe what they want to believe, and that’s all there is to it? The authors make an interesting statement about the implications for public presentation of scientific findings:

It is not enough to assure that scientifically sound information — including evidence of what scientists themselves believe — is widely disseminated: cultural cognition strongly motivates individuals — of all worldviews — to recognize such information as sound in a selective pattern that reinforces their cultural predispositions. To overcome this effect, communicators must attend to the cultural meaning as well as the scientific content of information.

The report suggests some ways that cultural meaning might be considered in communicating with the public. One such strategy is what the authors call narrative framing:

Individuals tend to assimilate information by fitting it to pre-existing narrative templates or schemes that invest the information with meaning. The elements of these narrative templates — the identity of the stock heroes and villains, the nature of their dramatic struggles, and the moral stakes of their engagement with one another — vary in identifiable and recurring ways across cultural groups. By crafting messages to evoke narrative templates that are culturally congenial to target audiences, risk communicators can help to assure that the content of the information they are imparting receives considered attention across diverse cultural groups.

AB — 24 Sept. 2010