I thought this was a great example of innovative thinking in the design of workshop gadgets — see (“Self-sorting (sorta) bin“). It’s a way to quickly store hardware items in the shop:

AB — 9 March 2010

I thought this was a great example of innovative thinking in the design of workshop gadgets — see (“Self-sorting (sorta) bin“). It’s a way to quickly store hardware items in the shop:

AB — 9 March 2010

The editors of Focus have created an interesting Infographic exploring the growing influence of open-source development, not just in software development, but in healthcare, science, content — even beverages (first time I’ve heard of OpenCola and Brewtopia Blowfly).

Focus is an open-source online resource for business data and research operated by media company Tippit Inc.

Here’s a link to the graphic — click through to see it full-size:

AB — 16 February 2010

One of the great challenges for an observer of public discourse these days is getting a clear, unbiased statement of both sides of an argument. People have powerful motivations to articulate only their opinion and trash the other side — see my previous entry, “Spin and Rhetorical Intimidation.”

So it was refreshing to come across the infographic linked below from Information Is Beautiful. The graphic provides a reasonable, neutral juxtaposition of both sides in the climate debate. (Click the image to see it full-size.)

AB — 8 December 2009

Reading Andrew Robinson’s fascinating book Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts (2002, McGraw-Hill), I recently learned the amazing story of the decipherment of the Linear B script by amateur philologist Michael Ventris in the 1950s.

The story brings home some important lessons about innovation:

Linear B is a script discovered on the island of Crete by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. Evans never deciphered Linear B, as he had fallen too much in love with certain precious ideas, chiefly his belief that the culture he had uncovered through his excavations at Knossos was a great noble civilization (which he called “Minoan”) that had dominated the Aegean in ancient times.

As it turned out, Linear B was a syllabic script used to write ancient Greek. However, the decipherment of the script was delayed by many decades because Evans was reluctant to share the inscriptions with other scholars.

When death finally wrested the inscriptions from Evans’s hands in 1941, other scholars were able to begin a concerted effort at decipherment.

Although it was Ventris’s genius primarily that cracked the script, he didn’t do it alone, which is a crucial point.

Although a brilliant scholar with a lifelong fascination for Linear B, Ventris was in fact not a professional philologist or linguist.

Ventris was an architect, and I think his architectural training, discipline, and practices were an important contributing factor in his success with Linear B.

Ventris was an architect, and I think his architectural training, discipline, and practices were an important contributing factor in his success with Linear B.

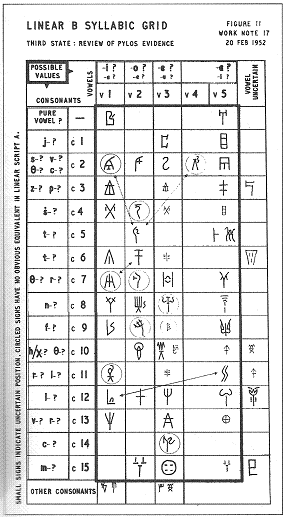

It’s interesting to note that Ventris’s grid-based system for decipherment is reminiscent of the schedules architects use to lay out information in their drawings.

But more important for Ventris’s success with Linear B was his value of collaboration, also an important architectural practice.

Robinson quotes classicist Thomas Palaima describing Ventris’s practice of “group working, hypothesizing and brainstorming” and adds that

In other words, he did not believe in the idea of the genius who works solo and finally solves a problem by his own sheer unaided brainpower …

Ventris explained in writing and in tremendous detail each stage of his attack on Linear B, and then circulated these neatly type “Work Notes” (Ventris’s name for them) to other scholars for comments and contradictions.

Much of what he hypothesized turned out to be irrelevant or wrong, but this did not stop him from showing it to the professionals. And it appears that he did take this whole approach from his work as an architect.

To me this stresses the immense value of multi-disciplinary teams, cross-fertilization, and collaborative approaches in all kinds of innovation work.

Also important was Ventris’s humility and willingness to recognize his own errors, in contrast to Evans’s stubborn insistence on his Minoan theory.

Ventris and other scholars had for a time favored the idea that Linear B was used to write the Etruscan language. However, after it became evident that the Linear B language was Greek, writes Robinson,

… in a measured and slightly diffident voice [Ventris] announced his discovery on BBC radio, publicly renouncing his long-cherished Etruscan hypothesis … As John Chadwick much later said of Ventris: “The most interesting fact about his work is that it forced him to propose a solution contrary to his own preconceptions.”

This is a worthy example for all experts, who are far too inclined to hop on a particular hobby-horse and just keep on riding it for their entire careers.

These lessons bring to mind some research that we have done at the Institute for Innovation in Large Organizations in the area of cross-functional teaming, a valuable process for innovation work.

(Most of our reports are limited-circulation and confidential. However, we do sometimes quote them as I will do here, and a few of our reports are available on request.)

Here are some points on the value of team diversity in product design from one of our reports:

Bringing people from many disciplines and functions together in design teams offers great potential as a strategy to produce innovative products. However, such diversity also lays the groundwork for conflict. Thus team leaders and company management need to manage team diversity so all members can be effective and make their contribution.

Mitzi Montoya, Zelnak Professor of Marketing at North Carolina State University (NCSU) and executive director of the Services and Product Innovation Management Initiative at the school, says that companies need to recognize the likelihood of conflict and miscommunication and “put processes in place that will manage that inevitable consequence.” The problems that arise from team diversity “have to do with how the organization is structured, who those people report to. It often has nothing to do with the project itself.”

Bob Pagano of Red Sky Insights points out that diversity can bring value to the product design process by putting blue-sky innovators in the same room with more hard-nosed practical players.

You’re going to have some people around the table who are really creative and are going to look at the assignment with a really open mind. You want to have some very creative people early on who might see something outside the normal way of doing things. If they say something really bizarre, we don’t necessarily want to discourage that.

But you also need some enforcers, the ones who are going to put up the barriers, the ones who will push back, but trying to reach a common ground. They might say, ‘Well, that’s interesting. Let’s see if we can do that within the rules on the retail end.’ It’s kind of a give and take to see that nothing gets overlooked.

In our ILO report, we also found that, aside from their contributions from a functional perspective, individual team members contribute different personal qualities to the life and work of a product design team. These different characteristics can offer value in unique ways and can come into play at different stages in the process:

Innovation consultant Stephen M. Shapiro, previously an Accenture consultant, believes that it is important to “understand the various innovation styles of team players” to make use of their distinctive strengths.

Speaking with ILO researchers, Shapiro explained how he classifies these styles:

Analytical people tend to be more focused on intellectual activities and often find flaws in everything.

Structured people want to know the plans and how things will be carried out. They also are a bit more critical but are more action oriented.

Creative individuals are cerebral yet like to think broadly. They are enthusiastic and generators of new ideas. But they are often poor at implementation.

Relationship-oriented people are needed to get anything done as they can engage the organization. But they often are too focused on consensus, which is a barrier to innovation.

Shapiro believes that “once people understand their styles and the associated strengths and weaknesses, they can be more effective in how they work together.” In his view:

The innovation process goes from analytical—define the problem . . .

to creative—define solutions . . .

to structured—define plans . . .

to relationship-oriented—engage the organization.

Thus, the various players’ personal styles can come to the fore at different stages of the group’s work.

But do team diversity and cross-fertilization translate into financial results?

Our work on this report suggested that that less diverse teams tend to produce better financial results overall than highly diverse teams. However, if the company is seeking high-value breakthrough results, it is more likely to achieve those through greater diversity in design team membership:

Lee Fleming, business administration professor at Harvard Business School, writes in Harvard Business Review that highly diverse, cross-disciplinary innovation teams introduce certain risks (“Perfecting Cross-Pollination,” September 2004). After researching 17,000 patents, he believes that

The financial value of the innovations resulting from such cross-pollination is lower, on average, than the value of those that come out of more conventional, siloed approaches. In other words, as the distance between the team members’ fields or disciplines increases, the overall quality of the innovations falls.

However, he adds a big but:

But my research also suggests that the breakthroughs that do arise from such multidisciplinary work, though extremely rare, are frequently of unusually high value—superior to the best innovations achieved by conventional approaches.

Fleming comments that “when members of a team are cut from the same cloth,” as with a group of all marketing professionals, “you don’t see many failures, but you don’t see many extraordinary breakthroughs either.”

However, as team members’ fields begin to vary, “the average value of the team’s innovations falls while the variation in value around that average increases. You see more failures, but you also see occasional breakthroughs of unusually high value.”

AB — 21 Nov. 2009

TED Talks has posted a video of neurologist Oliver Sacks discussing hallucinations — particularly Charles Bonnet hallucinations, which occur among many visually-impaired people.

Oliver Sacks is known for his investigation of neurological disorders that result in bizarre experiences and behavior. One of Sacks’s early books was calledAwakenings, which was made into a movie of the same name, with Robin Williams playing a doctor based on Sacks, and Robert Deniro playing a catatonic patient who ‘comes back to life’ through an experimental treatment.

Some of my favorite Sacks books are The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat andAn Anthropologist on Mars. Sacks is a great writer, and his books are very entertaining as well as informative.

The video is about 18 minutes — see “Oliver Sacks: What Hallucination Reveals About Our Minds.”

AB — 17 Sept. 2009

I recently completed two books by two very different authors, Douglas Rushkoff and Benjamin Wiker. However, the serendipitous fact that I read them one right after the other brought home to me some intriguing commonalities between the two, focusing particularly on the widespread societal effects of social darwinism.

The two books are:

Although I suspect that these two authors would be very far apart on political issues, my reading of these two books in juxtaposition emphasized two interesting commonalities:

In writing the above, I also came to an interesting realization on another more-subtle commonality: Wiker starts with the classic cynical treatise The Prince, by Niccolo Machiavelli. Rushkoff starts with the Middle-Age “princes” who created the corporation and imposed central currency in Europe.

Rushkoff’s premise is that the aristocracy in the Middle Ages devised the chartered corporation as a legal mechanism to give them control over commerce and wealth. Because of their privileged status granted by government, corporations have progressively gained more power, even becoming legal “persons” over time.

Rushkoff’s criticism is that Western society has become steeped in corporatism, and that this pits individuals against one another in a win-lose competitive struggle. People operate according to unconscious corporatist values and assumptions about how life should be and are prevented from connecting in a natural way through communities.

Wiker’s premise is that modern civilization has been affected by a materialistic, atheistic philosophical tradition preserved and promoted by a series of highly-influential thinkers and their books, starting with Machiavelli, then Thomas Hobbes, Rene Descartes, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, Margaret Sanger, Margaret Mead, and Alfred Kinsey, along with others along the way.

As I said, where I see an important commonality between Rushkoff and Wiker is when it comes to their implications and comments about social darwinism: The modern world is strongly influenced by the idea that the natural order demands that the strong survive and the weak die off.

Ruskoff writes,

Richard Dawkins’s theory of the “selfish gene” popularized the extension of evolution to socioeconomics. Just as species competed in a battle for the survival of the fittest, people and their “memes” competed for dominance in the marketplace of ideas.

Human nature was simply part of biological nature, complex in its manifestations but simple in the core commands driving it. Like the genes driving them, people could be expected to act as selfishly as Adam Smith’s hypothetical primitive man, “the bartering savage,” always maximizing the value of every transaction as if by raw instinct.

Ironically, says Rushkoff, religionists were used to promote a compatible economic regime:

Right-wing conservatives turned to fundamentalist Christians to promote the free-market ethos, in return promising lip-service to hot-button Christian issues such as abortion and gay marriage.

It was now the godless Soviets who sought to thwart the Maker’s plan to bestow the universal rights of happiness and property on mankind. America’s founders, on the other hand, had been divinely inspired to create a nation in God’s service, through which people could pursue thier individual salvation and savings.

Rushkoff contends that

What both PR efforts had in common were two falsely reasoned premises: that human beings are private, self-interested actors behaving in ways that consistently promote personal wealth, and that the laissez-faire free market is a natural and self-sustaining system through which scarce resources can be equitably distributed.

Wiker follows the development of atheistic social darwinism from Machiavelli, but he takes considerable time to establish the connection between Darwin and eugenics. On pages 88 to 89 of 10 Books he quotes from Darwin’s Descent of Man (not as well known as On the Origin of Species):

With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health …. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination [by means of various works of charity and relief]. Thus the weak members of civilised societies propagate their kind ….

If … various checks … do not prevent the reckless, the vicious and otherwise inferior members of society from increasing at a quicker rate than the better class of men, the nation will retrograde, as has occurred too often in the history of the world.

Wiker argues that the writings of Darwin and other atheistic thinkers have led to a modern world in which the weak are seen as expendable for the good of human progress.

At the end of his book, Wiker comments:

We are so fond of thinking of our progress from the simple savage that we forget to take account of whether we are really progressing in some sort of virtue or rather becoming more complexly and deviously savage.

We have a higher regard for health than our ancestors did, and a far greater knowledge of biology. But when biology, rather than theology, becomes the queen of the sciences, then Christian prohibitions against eugenics, the elimination of the unfit or the unwanted through abortion or infanticide, or the elimination of diseased races or classes all become merely “medieval” and irrelevant.

Rushkoff and Wiker approach their analyses with very different objectives and foci, and it would be far from accurate to say that they reach the same conclusions.

But both Life Inc. and 10 Books That Screwed Up the World shine light on some of the historical and philosophical sources of the great streak of heartlessness evident in the modern world.

In about 1970, I was picked up hitchhiking on I-85 in North Carolina by an older fellow driving a sedan. We got into a conversation about the problems of the world. From his point of view, one of the biggest problems was welfare and charity — all the giveaway programs that are supposed to help the poor.

I raised the question, Well, what are they supposed to do? Suppose they need help to survive and get back on their feet?

His response was, “Who cares? Let ’em die. That’s the way nature works.”

I wonder who he had been reading.

AB — 4 September 2009

Just yesterday I read on The Watchismo Times (a blog dedicated to unusual timepieces) about a new mechanical wristwatch designed with a linear time display rather than the traditional circular clock face. (See “Urwerk King Cobra CC1 Reintrepretation of 1958 Patek Philippe Cobra Prototype – Cylindrical Retrograde Linear Jumping Hour Display.”)

This design is thought-provoking: We normally conceive of time as a line, and yet for centuries the standard timepiece interface has been a circle. The author of the Watchismo site explains why this is:

Why do we think of time as travelling in a straight line yet display it rotating around a circle? The answer is straightforward: mechanisms that continually rotate are much simpler to produce than those that trace a straight line then return to zero. In fact, the latter is so difficult that, until now, nobody has ever managed to develop a production wristwatch with true retrograde linear displays.

It makes me think about how I conceive time personally. In the big picture, I think I do see time as a straight line going infinitely to the left and right.

In spite of the more linear design of the calendars I use, I believe I conceive of the calendar as a circle, as if the year were superimposed on a standard clock face. However, in my mind, the calendar runs counterclockwise with January at approximately the 11:00 position. I think my circular conception of the calendar comes from the periodic nature of the solar year. Why the year goes counterclockwise in my mind I don’t know.

When it comes to my conception of days, though, I see some ambiguities. I do conceive of them on some level as a circle of 24 hours, but on reflection I think that conception is at least partly based on the circular clock faces we use to keep time, as well as on the collective 24-hour standard we use to keep our society synchronized.

Certainly the new Urwerk King Cobra CC1 provides food for thought about how we think about time and about the user interfaces of the devices we use to keep track of it. Below is a link to Watchismo’s picture of the watch. Watchismo also provides many fascinating details about how the watch is designed and constructed.

AB — 10 July 2009

Robert S. McNamara, who was Secretary of Defense under U.S. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, died yesterday at age 93 — see today’s article in The Washington Post.

As a teenager during the Vietnam war, my view of McNamara was two-dimensional, you might say. For the black-and-white morality of a young war resister, he was the enemy.

Years passed, and I didn’t think about Robert McNamara much until 2004, when the documentary The Fog of War – Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara came out.

Watching the movie, I was fascinated at the nuanced picture it presented of this once-controversial and divisive figure. The film includes comments from a long interview with McNamara. It would be over-simplifying to say that he admits he and other policy-makers were wrong in the way they prosecuted the Vietnam conflict. He really gives the viewer a sense of how hard it is for decision-makers to be certain they are doing the right thing.

Watching and listening to McNamara in his late-80s, I also remember feeling some shame at my previous attitude toward this somewhat stooped old fellow in his tan raincoat.

Can’t remember where I read it, but it was good advice: If you find yourself hating someone, try imagining them as a helpless little baby or as a very old person near the end of their life.

AB — 6 July 2009

[Note: This is another essay/memoir I wrote awhile back and just rediscovered. Decided to publish it here on Quriosity to give it the exposure and adulation it deserves. AB — 26 June 2009]

The American Dream

A memoir, mostly true, from Spring 1972

by Al Bredenberg

Oct. 10, 2006

Melissa (not her real name) walked with me across the quadrangle after our American Literature class. The sun shone on her curly brown hair through the tall oak trees, their leaves bright green in their early spring growth. Melissa had very large brown eyes and an ample figure that filled out in a pleasing way the tight dress with low-cut rounded neckline, a bright floral print on crinkly fabric like crepe paper.

I asked her to go out with me and was happy when she said she would.

The night of our date, I walked to Melissa’s dorm from the house near downtown Chapel Hill where I lived with my friends John and Linda. Melissa lived in Granville Towers, not exactly a dorm — more of a quasi-off-campus apartment tower for kids with a little more money. When I had lived on campus my first semester, I had lived in Avery, one of the plebe dorms on campus.

Melissa was what at the time I would have called a “straight girl.” I didn’t go out with many straight girls, but Melissa was very pretty and nice to talk to — a doll with cheerleader good looks. And when I asked her out she said yes, so that was a positive sign. That usually didn’t happen with straight girls.

To be honest, I don’t remember much about that date. Knowing my financial situation at the time, I doubt if we did anything that cost money. I do remember that Melissa dressed down for me, wearing jeans with a white blouse. I do remember walking together; there’s a real possibility that the entire date consisted of walking around Chapel Hill and the UNC campus. I remember I told her about the meditation and yoga classes I had been taking from Ananda Marga Yoga Society and about my recent initiation with an Indian teacher called Dadaji. Hearing all of this, Melissa listened politely but didn’t have much to say. I can’t imagine what she thought about this skinny, long-haired, bearded oddball with the expanding consciousness.

Besides American Literature, I was taking Latin, Music Appreciation, and Creative Writing. In American Literature we were studying The Great Gatsby — my second try at this novel, as it was one of the ones I was supposed to have read as a junior in high school.

One day, not long after my date with Melissa (not her real name), our professor, Dr. Allen (not his real name either) started using the phrase “the American Dream” during our Great Gatsby discussion. That phrase actually sneaked out of his mouth and drifted around the room two or three times before it slithered past me and got my attention. He used it in a familiar, pat, matter-of-fact sort of way, but I wasn’t about to let him get away with it.

“What do you mean by ‘the American Dream’?” I blurted out.

Dr. Allen leveled a smug gaze at me, a hint of a smile pulling up the corners of his mouth. He explained the concept in a soothing voice: “It’s the goal we all have as Americans: to achieve wealth and success through hard work and competition.”

I sat back, eyes wide, jaw dropping. “You’re joking, right?”

The silvery, balding professorial head tilted slightly. “That’s what we’re all looking for. That’s what happiness is all about, isn’t it?”

“Nobody really believes that, do they?” Titters arose from around the classroom. I glanced around at my classmates.

“That’s why you’re all here at college. To get an education, get a good job, get ahead in the world.”

“That’s crazy,” I said. “Nobody really buys that, do they?” More titters and a few guffaws. Dr. Allen smiled down indulgently. I glanced wildly around the classroom. “Is that what you all think? Do you really think it’s going to make you happy to make it in this world and get rich?” Their expressions gave me the answer.

“So did you think that was funny?” I asked Melissa after class, as we walked across the brick courtyard in front of the bookstore. Big round eyes, full face, rounded figure. She smiled and nodded.

It came to me that this was going to be my last semester at UNC, even though I loved learning and I was making good grades. I was going to finish the semester in a few weeks and go get a job as a carpenter.

“Why are you here at school?” I asked her.

She shrugged and spoke in a matter-of-fact, ‘well, of course’ tone: “So I can get a job and make a lot of money.”

“Is that really what you think is going to make you satisfied?”

A puzzled smile on her luscious mouth. So beautiful it hurt to look at her. “Well, sure.”

“I don’t believe in it,” I said. “It’s not real.”

Large brown eyes glistening. “I don’t understand what you mean,” said Melissa. Not her real name. Actually, I don’t remember her real name.

AB — Written 10 October 2006, posted here 26 June 2009

[Note: The following is an essay I wrote in December 2003 put never published anywhere. I just ran across it and thought I would post it on Quriosity.]

Two months ago I stood in a cemetery in Wilton, Connecticut, looking down at the shiny wooden coffin containing the body of my wife Virginia’s uncle, Paul Lyon, soon to be lowered into the dug grave and covered with earth. Nearby the coffin stood an easel bearing a montage of photos from Uncle Paul’s life mounted on a sheet of poster board. A good breeze was blowing, so my chunky teenage nephews, Kellen and Tristan, trussed uncomfortably in neckties and sport jackets, stood flanking the easel like a pair of ushers, holding either side of the cardboard sheet to keep Uncle Paul’s pictures from sailing away on the wind.

I’m a real crybaby, and that day was no exception; I thought about the cold body inside that wood box — a man I had known and liked, an affable man of my parents’ World War II generation, who had lived what I supposed was a basically decent life.

Two photos stuck to that cardboard matting also stick in my mind from that windy day in the cemetery:

One, a picture of Paul Lyon sleek in his airman’s uniform during the war, not much older than my willowy 20-year-old son Paul (named more for my father than for my wife’s uncle, and named even more for the apostle than for any relative).

The other, a photo of Paul Lyon at age 80, only a few weeks before his death, standing at his front door waving goodbye. Maybe when he lifted his hand to the camera for that wave, he had in mind the cancer that was spreading inexorably inside him.

I think a lot about life and death, and I find myself again and again coming back to photos and to numbers. I told you about some photos; now consider some numbers: At 52, I stand right about between son Paul and uncle Paul: age 20, age 50, age 80. Thirty years back and I am my son’s age, hitchhiking across the country with a duffle bag, tambourine, and five dollars in my pocket. Thirty years ahead and I am lying in a wooden crate.

I love to look at old photos from the 19th century, to leaf through a book and muse on the faces of people from that time. Their faces are fresh, the spark of life is in their eyes. In a moment, this man, I imagine, will turn from the camera, kiss his wife, walk home with her, have dinner, go to bed, and make love.

In reality, he is long dead, a pile of bones under the ground. In fact, all of these faces are gone, carried away on the wind across a cemetery. They are all dead, every single one. Maybe nobody now living remembers them or even knows their names.

And of course, the thing that I am trying to grapple with, to force myself to confront, is that, in the normal course of things, mine will become a face like that. Someone will look at my face in an album, wonder briefly who I was, then flip to the next page.

You should understand that I am speaking as one who believes that this life is not all there is, that there is a higher being who cares, who remembers us and will bring us back. And that belief underpins my life so I can live hopefully. But it doesn’t completely do away with the visceral reaction to the enveloping death that is moving toward me to cover me over and draw me down into the unthinkable sleep. It will flow over me, and I will be gone. How can there be a world, if I am not in it?

Last week I got in my car to drive up to New Hampshire to my consulting job at a graduate school in Keene. The Public Radio program Morning Edition was on, and because of the proximity of Christmas, the interviewer was speaking with bookstore managers across the country asking for recommendations of good books for gifts.

One store manager recommended a book called “When It Was Our War,” and my stomach dropped when I heard the name of the author, Stella Suberman. Jack and Stella Suberman were friends of my parents when I was growing up in Raleigh, North Carolina. I remember watching them play tennis with my mother and father, and I remember swimming in their pool, and I remember them from dinner parties and cookouts. They were two larger-than-life people, awe-inspiring and wonderful and frightening (well, Jack was scary, anyway — Stella was bright and beautiful and charismatic).

One of the devastating moments in my life (among many, admittedly) was when I told my mother I wanted to invite the Subermans to come to my high school graduation and she waved off the idea — the Subermans don’t really know me that well, she said, and they would think it odd if I invited them to my graduation. Suddenly I learned I was nothing in the eyes of these two marvelous people who had been giants to me.

So, sitting in the car last week, hearing a recommendation of Stella’s World War II memoir, I was affected … well, as I said before, I’m a real crybaby. First chance I got, I ordered a copy of “When It Was Our War” from Half.com and started reading it this week.

Reading Stella’s book I become a time traveler. It’s a story of the young wife of a soldier during the war. The fascinating thing is that I am peering into the lives of two people, important in my childhood, before I ever knew them, before I was even born. On the cover of the book are black and white photos, a small one of Jack in his uniform, a larger one of a gorgeous Stella in a short tennis skirt, leaning against a palm tree. In the photos, Jack and Stella are easily recognizable as the people I knew. Seeing their faces, I can hear their voices on the tennis court and by the pool.

But reading Stella’s reminiscence and seeing these photos gets me going playing with numbers as I am wont to do.

In these photos, Jack and Stella are about 20, the age my son is now. But they are actually the contemporaries of my father and Virginia’s departed uncle. So I can peek in on their lives and see them practically as children. When I knew them 15 years later, they seemed old and formidable to me. But even at that age, they were in fact youthful in comparison with my now ancient age of about 50.

So I take these odd jumps of 15 years backward and forward along the line of my life and that of the Subermans and somehow it emphasizes to me how fleeting it all is, while yet so rich and wonderful.

Here’s another game with numbers: I was born in 1951. Go back about five years and you’re at the end of the Second World War, which doesn’t seem that long ago to me but would to my 20-year-old son. Go back just 35 years from 1951, and you are at the end of the First World War. That does seem like a long time ago to me, but it’s a relatively short period of time compared to the 50 years that have passed (quickly it seems to me) since 1951.

I wonder if I’m making any sense.

What it kind of amounts to is that I am like the character Dave in the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey”: I’m a middle-aged man looking back at myself as a young man. But standing in the doorway is an old man, also myself, watching me as a middle-aged man. The whole thing passes in a flash. Day by day, the experience is sweet and incredibly deep. But all in all, 80 years is very short.

As we drove away from the cemetery in Wilton, I told my sister-in-law Natalie and my nephews, “You know, the Bible says it’s good to go to a funeral. And it says that the day of your death is better than the day of your birth.”

Natalie was intrigued by the idea. She thought maybe I was referring to the cycle of life, but that wasn’t what I had in mind. The point is that when you’re born, you could turn out to be anything at all, good or bad. But at your death, you’ve had a lifetime to show what kind of person you are — what you made out of that thin thread of years as they spun their way out.

It’s Ecclesiastes 7:1, 2 I was thinking of: “A name is better than good oil, and the day of death than the day of one’s being born. Better it is to go to the house of mourning than to go to the banquet house, because that is the end of all mankind; and the one alive should take it to his heart.”

So I look through the pages of photos and run through the numbers in my head. And I try to take it to heart. Because I can feel the wind picking up, and all-in-all I’m not much more than a picture taped to a piece of poster board.

AB — written December 2003, posted 26 June 2009